| In 1967, the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) opened its brand-new campus in Johnstown, Penn. One of Pitt’s small extensions in rural Pennsylvania, Pitt-Johnstown had operated out of the Moxham section of town since before the World War I, providing continuing education to the surrounding areas. In response to growing demands for higher education, Pitt built a brand-new campus in suburban Johnstown and relocated operations there. Even though the opening of a small branch university campus normally attracts little to no attention, Pitt-Johnstown received national media attention disproportionate to its size. This widespread attention was attributed to its “Heat Reclaim” system produced by the Carrier Corporation, which allowed the campus to collect and store waste heat – from its central air conditioning system but also from body heat – that could then be used as heating source during the winter months. |

This set of curatorial materials uses Pitt-Johnstown as a springboard to tell the social history of “heat reclaim” technologies. Despite the media attention on Pitt-Johnstown, it was not the first time such system had been implemented (either by retrofitting existing buildings or by building it in new constructions); it was not even the first time Carrier installed such system in new constructions. In fact, the concept of heat reclaim was first proposed way back in 1805 by Oliver Evans, and the first such system – as small as it was back then – was produced in 1855 by Peter Ritter von Rittenger in Austria. The basic premise is simple: “a refrigeration system transferred heat from a lower energy state to a higher one” and thus, could potentially “be used for heating purposes.” This type of technologies became known as “heat pumps,” but they were never very popular; as Donaldson and Nagengast argued, they “had to compete with fossil-fueled heating systems, which themselves were becoming increasingly more reliable and lower in cost.”

Donaldson and Nagengast’s Heat & Cold ended the history of indoor air conditioning and environmental control in the 1930s, with a section on the forgotten history of heat pumps. This editorial decision suggests a number of curious questions: If heat reclaim technologies have such a long history and are arguably more sustainable than other air conditioning technologies, why did it lay dormant for so long until the 1960s? What is it about the 1960s that allowed – and perhaps pushed – Carrier to excavate this old concept and brand it as its own new innovation? And what are some of the previous heat reclaim technologies integrated into building designs that the archives of air conditioning have overlooked? The Carrier archive on projects like Pitt-Johnstown can help address some of these questions.

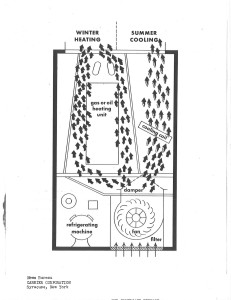

| A diagram that shows the basic logic behind a Carrier heat pump: it is not exactly “heat reclaim” yet as it does not store excess and waste heat. Donaldson and Nagengast offered the most obvious answer, that heat reclaim technologies came from a different industry and had a different geography. Much of the initial research and production of heat pumps were in Europe, done by companies that were interested in both heating and producing energy. This focus on energy production shaped the development of heat reclaim technologies, as the first companies stateside to make heat pumps were all energy suppliers: the Southern California Edison Company in 1931, the Atlantic City Electric Company in 1934, and the “first successful package heat pump [with air-cooling systems] was… produced by the De La Vergne Division of Baldwin-Southwark Corporation” in 1933. |

The other part of Donaldson and Nagengast’s explanation – arguably the more influential part – is also evident from the Carrier archive. Heat reclaim technologies are an early incarnation of sustainable technology; it quite literally ‘reclaims’ the waste heat produced during mechanical processes and distributes it as heating source. As the authors alluded to, cheap fossil fuels meant that the incentive to promote sustainability was low, and heating and cooling remained largely separate industries. This meant that for Carrier, heat was a nagging problem to be dealt with in the cooling process. The most obvious fact about air conditioners is that it is supposed to cool down the heat. But to accomplish that task through a mechanical process requires a lot of energy and – incidentally – produces a lot of heat. Carrier had two issues with heat: How to provide relief from the external environment to its technologies (primarily through preventing radiation)?; and How to remove heat produced by its technologies from the systems in which they operated in (i.e., waste heat)? Initially, Carrier’s attention was on the former, so that its engineers took inspiration from people like architects, who have studied things like how to orient a structure or what sorts of glass to use for windows in order to maximize natural lighting but not overheat the interior. Small’s article cover here exemplified this approach.

Gradually, however, the attention began to redirect toward the latter. Traditional A/C units were already pumping out waste heat to the external environment. A new design approach, squeezed by calls to be more economical and more sustainable, began taking heat as an object of analysis seriously. What happens when one can redirect the waste heat? We see this historical transformation within Carrier (and the air conditioning industry as a whole) most clearly from the two contrasting reports from Bartlett Small and Neil Hill; one advocated for relief from heat, while the other championed heat reclaim. Ultimately, as Hill argued, the heat reclaim technologies won out, and projects like Pitt-Johnstown began emerging in the 1960s.

This set of visual materials, then, documents the historical conditions that led to Carrier’s adoption of heat reclaim technologies. It includes samples of early Carrier heat pumps, articles that fought on the two sides of heat problem, other installations of heat reclaim technologies in the 1960s (focusing primarily on educational institutions), and finally the Pitt-Johnstown campus. Through these materials, one can begin to see how a particular technology comes to inform what Catherine Fennell calls “sensory politics.” Although she never explicitly defines the term, I think we can see how an ‘object’ like heat is continuously reconfigured first as waste then as commodity; but those reconfigurations are not simply achieved through political-economic shifts, but in part through how people understand, define, and ‘sense’ comfort temperatures. Fennell argues that the politics of public housing demolition is at its core a question of “how neoliberal demands for self-responsibility have become tied to demands that transitioning residents reconfigure their subjective senses of comfort.” In some ways, the transition to heat reclaim technologies – in schools, especially – had asked people to do the same with indoor heating. While urban revitalization and neighborhood redevelopment were the justification for public housing demolitions, sustainability helped rescue heat reclaim technologies from the history books and into our schools and homes. It is the beginning of a logic that, although students might not know it consciously, had nonetheless physically participated in the production of “a new moral here… about the value of going to college”: that is, as sustainable citizen-consumers trading body heat for the right to education.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed